Starting a new business can be an exciting time, with lots to think about. One of the earliest and most important decisions you will make is what business structure to use.

Choice of business structure impacts your potential tax and legal liability and influences how clients, competitors and potential employees perceive your business.

This short guide will explain the differences and help you make the right decision.

What are the different types of business structures?

There are basically five different types of structure used for setting up a business:

- Sole trader – where you carry out the business personally, either under your own name or a trading name. It’s the simplest structure to understand and the easiest to set up.

- Company – a company is legally a separate entity from you. It has shareholders (owners) and is run by directors, who are appointed by the shareholders. For most small businesses, the directors and shareholders are the same people. A company provides you with some additional protection from liability but comes with extra administration and complexity. Companies are governed by the Corporations Act and are taxed separately.

- Partnership – consists of two or more individuals or companies who join forces to share in the profits and losses of a business enterprise. A partnership is not a separate legal entity, so each partner can be responsible for the debts of the partnership and risk is shared “jointly and severally”.

- Trust – a legal relationship, where one person (the “trustee”) holds the business assets “on trust” and manages the business for the benefit of others (the “beneficiaries”). This is the most complex form of business structure, but can provide additional benefits.

- Joint venture – an arrangement where two or more parties pool their resources and work together towards a specific outcome. Unlike a partnership (which is usually used for an ongoing business), a joint venture is often used just for a single project or as a temporary arrangement. This type of structure is uncommon for small businesses.

Only the first four are taken into account for tax purposes because tax law doesn’t recognise the concept of a joint venture.

Remember too that you can combine different legal structures to achieve your business and financial objectives. For example, you might decide to establish a company to run your business, but with the company owned by a trust. Another option might be to have a partnership of companies, where each partner is itself a company.

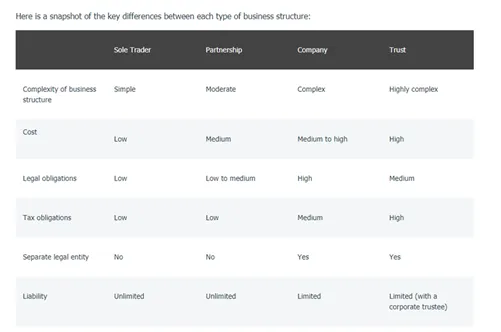

What are the key differences between each business structure?

Each business structure has its own unique advantages and disadvantages.

Sole trader

Running your business as a sole trader is the easiest structure to set up and the least expensive too. The business is set up under your own name (although you might have a separate business or trading name too). You will also enter into any contracts, debts, business commitments, and so on, in your own name. You can also hire employees, open separate bank accounts and do all those other things a company would do. This makes you personally liable for any commitments of the business, which could put your personal assets at risk. For example, if you get into a dispute with a customer or supplier and they decide to sue you.

As a sole trader, you have far fewer reporting requirements than under other business structures, which helps reduce compliance costs. However, you still need to lodge a personal tax return and you’ll be liable for the tax on the business profits. You will also need to lodge a Business Activity Statement if you are registered for GST.

Company

When you establish a company, you are creating a separate legal entity. A company has shareholders, who are the owners and directors, who are legally responsible for the company. In most small businesses these are the same. The company can enter contracts, incur debts or other liabilities and sue other people or companies, or be sued itself.

This is all separate to your own personal liability. As the owner and shareholder of a company, your own liability is effectively limited to the value of your shareholding (although you can incur personal liability as the director of a company in some situations). This limited liability is one of the main benefits of operating under a company structure.

The trade-off is that it takes some time and cost to set up a company and to manage its annual compliance requirements. The company will need to comply with the Corporations Act, keep proper financial records and lodge a separate company tax return with the ATO.

As the shareholder of the company, you get the profits of the business by way of dividends. In the Australian tax system, there are advantages to dividends because you also get any attached franking credits. This means the income you receive already has tax paid on it, saving you money.

Companies are an extremely common business structure and may give your business more credibility with suppliers, customers, employees and investors.

Partnership

Under a partnership, two or more people agree to work together to run a business and to share the profits (or losses) between themselves. The partners will often enter into a Partnership Agreement, setting out how the partnership will be managed. Depending on the type of partnership, each partner can have unlimited liability for the debts of the partnership (a “general partnership”) or have liability up to a limit based on how much they have contributed (a “limited partnership”). It’s also possible to have an Incorporated Limited Partnership (ILP), although this needs to have one general partner who has unlimited liability.

A partnership is not a separate legal entity (in the way that a company is) but is treated separately from its partners for tax purposes, which means the partnership must apply for its own TFN and lodge a partnership tax return. However, the partnership doesn’t pay income tax – instead, each individual partner pays the tax on their share of the net partnership income.

Trust

Under a trust arrangement, the trustee holds and manages the business assets on behalf of the beneficiaries. Often the trustee will itself be a company, which helps the owner limit their liability and protect their personal assets from any potential claim.

To form a trust, you will need a Trust Deed that sets out how the trust will operate. Establishing the trust and complying with the annual compliance requirements usually makes a trust the most complex and expensive of the different business structures available. However, the benefit for business owners of a trust arrangement is that it can provide a lot more flexibility for tax purposes and personal financial planning. As with a partnership, the trust will also have its own TFN and is required to lodge an annual income tax return.

Joint venture

A joint venture involves two or more businesses working together towards a shared goal. Each business remains separate, and maintains its own independence, but agrees to work with the other business (or businesses) towards a combined project or objective. In that sense, it’s like a partnership but it is not usually an ongoing arrangement and the parties will end the joint venture when its objectives have been achieved. The parties will usually have signed up to a Joint Venture Agreement that sets out their obligations and details of how the joint venture will be managed. That will also set out how they are going to share the profits of the joint venture.

The tax system does not recognise joint ventures, so each party in the joint venture will normally be required to lodge its own tax return. However, the tax implications of a joint venture can quickly become complicated, and it is always best to obtain specialist advice as to how being part of a joint venture will affect your own situation.

Which structure is best for my business?

The choice of structure will depend on your aims for the business. If you start small and intend to remain a side-hussle, then a sole trader is the best way to go. If you want to raise capital, you need a company. Want to enter into business with other people? Then a trust or partnership would be a good option to consider.

The table below provides a helpful summary of the key differences between the different types of structure:

What are the registration requirements for my business structure?

When setting up your business, the choice of business structure will determine the various applications and registrations you will have to make and obtain – such as getting an ABN or TFN, registering for GST or other taxes, and registering with ASIC.

For a quick guide to help you with the terminology and to work out what business registrations you will need, please see our previous article: Registering your business.

Download our FREE Profit First calculator

We have built a fantastic Profit First calculator. Its been designed for Australian conditions and takes into account GST, PAYG and other amounts. Click here to download.

Many people who are would-be business owners think that one set of principles apply to personal finance and a whole other set of rules come into play when you’re dealing with a business.

But think of it this way: Whether you’re just trying to lose weight, or you’re training for an Ironman, the same essential and common sense practices apply. You would eat right, train hard, and rest up.

The same is true for building businesses. The truth is that you can’t make money appear out of thin air and you can’t expect to create consistent profits with no plan for prioritizing profits.

Fact: Most businesses operate under the mindset that, “When I make more money, I’ll be able to generate greater profits.” The answer, then, is to first shift that mindset or that fallacy, and to follow that up with aligned actions that ensure that you’re focused on profits first.

Key Takeaways From Profits First

Mike Michalowicz wants businesses to return to the tried-and-true truths of good business accounting and sound financial principles. And in the world of basic proven formulas, perhaps the simplest is its most foundational: Sales – Expenses = Profits.

But if it’s the cornerstone of business, why do so many businesses disregard it? Worse still, why do businesses that employ this formula end up with a cash flow management system that lacks the main component: cash?

As the name implies, Profits First charge you, the business owner, to focus on profits first. It flips the conventional equation on its head and encourages you to think about winning (rather than covering loss). This profound psychological mindset shift makes profit the focus of all your business and accounting activities.

For Mike, the winning equation looks like this instead:

Sales – Profits = Expenses

So here’s takeaway number one: Take profits first.

That’s because money is oxygen to businesses. Without enough money to operate, we can’t take our products and services out into the world. Instead of being business owners, we end up being slaves to our own businesses.

What is the Profit First Method?

The Profit First Method is both a system and a practice. It allows you to create long term success in a sustainable way, growing naturally to a size that?s right for your operations and your team. In the meantime, your system demands that you account for profit first, then taxes, and then your own pay.

The amount left over is what the company spends on everything else (i.e. expenses). Accountants and finance-heads will recognize this as the basis for good old fashioned envelope method. But it’s a classic and that’s why Michalowicz calls it a system that will “transform your business from a cash-eating monster to a money-making machine.”

So how do you get to this promised land of the constant cycle of profits?

This is your second takeaway: by exercising discipline and setting limits in the same way you would with portion control for your diet.

You set aside a percentage of your revenue as profit. Once you eliminate taxes and the price of paying yourself (and making payroll), the amount of money you’re left with will be lean. And that’s how you’ll be forced to get creative, rethinking the “must-haves” from the “nice-to-haves.”

Suddenly, expenses like the cost of materials, rent, utilities, etc. are negotiable. It sounds uncomfortable and any business owner will tell you that it is.

It’s designed to feel this way.

Because, eventually, as you keep focusing on profits and moving forward, you’ll grow your business without endangering it or, worse still, burning yourself out.

So here’s takeaway number three: Debunk the idea that putting every spare dollar back into your business as an investment for the future. It’s actually a risky action that could cost you in the event of a future crisis.

The Four Core Principles of Profit First

The four core principles of Michalowicz’s Profit First undergirds all actions you’re going to take moving forward.

Keep these in mind whenever you feel a sense of resistance against implementing the Profit First system (which we’ll take a look at later in the summary).

1) Parkinson’s Law is Always at Play

Parkinson’s Law states: The demand for something expands to match its supply. This applies to time and money. And, in both cases, this is not a good thing.

So to counteract the reality of money, where the more we have, the more we spend, you need to intentionally keep less around so less is available.

2) Don’t Forget the Primacy Effect

Why does it matter that “profit”comes before “expenses” in the new-and-improved formula? It’s the primacy effect. What you prioritize we expand. So if you make money to cover expenses, you’ll meet more expenses.

But if you’re operating to expand profits, then you leave the Sisyphean cycle of rolling that business boulder to the top only to have it roll down again.

3) When it Comes to Temptation, Out of Sight is Out of Mind

To help you keep Parkinson’s Law at bay, consider this maxim: out of sight is out of mind. If you keep your money out of direct access then you won’t be tempted to access it.

Once it’s out of sight, you’ll work with what you have rather than worry about making what you don’t already have.

4) Establish a Rhythm

One of the behaviors that businesses (and business owners) that focus on expenses get trapped into is a reactive mode. Crazy spending is followed by big deposits, and then panic when cash dips.

Instead, you need to establish a reliable rhythm tied to consistent and sustained cash flow. When you need to check your cash flow, all you’ll be doing is check your accounts (more on this as you read through the rest of the summary).

The Mindset Behind a New Accounting Formula

This entire section is highlighted by the following quote:

“Businesses that plow back their profits aren’t truly profitable; they are just holding money temporarily (feigning profit) then spending it, just like any other expense.”

Once you begin using the new accounting formula, you’ll gain clarity on money-making versus money-draining activities. From here, it’s simple once again: Do more of what works and fix (or let go of) what’s not working.

Here’s how you should apply the new accounting formula.

1) Use Small Plates

As you put the Profit First method into action, you’ll set up a number of accounts, each with their own purpose and function. One of these is the INCOME account.

Money comes into your main INCOME account, but its only a holding tray. From here, you distribute the money through the other accounts in preset percentages. These are your small plates.

2) Serve Sequentially

This relates back to the “rhythm.” If you keep to a sequence of allocations, it will quickly become a practice. Once it’s a practice, it’s a habit. And once it’s a habit, you will do it on auto. For now, though, resist thoroughly the “temptation” to pay your bills first.

Instead, set up a sequence of payments where you allocate money based on the percentages, to the following accounts:

-

- PROFIT account

- OWNER’S COMP account

- TAX account

- OPERATING EXPENSES (OPEX) account

This last account is the only one that you’re allowed to use to pay bills. No exceptions.

If you fall short, you know you need to either evaluate your expenses or drop what is clearly unnecessary.

3) Remove Temptation

The key to temptation is accessibility. So keep your PROFIT account out of arm’s reach. You can do this by giving authority to a finance professional to act on your behalf or make it really painful and tedious to borrow from (perhaps setting up multiple permissions). You can also use an external accountability partner that you have to check-in with.

4) Enforce a Rhythm

The “rhythm” you’re setting up relies on the accounts you’ll establish. But there also needs to be a rhythm (or reliability) when it comes to taking action. That’s how you remove the element of (unpleasant) surprise.

-

- Allocations and payables should occur twice a month (Michalowicz suggests the 10th and the 25th).

- Don’t pay only when money has piled up. Instead, see how and when cash accumulates, and where the money goes each time you pay out.

How to Set Up Profit First For Your Business

This part of Profits First is the meat and potatoes of the entire book. It gives you a detailed, step-by-step account of how to implement a cashflow accounting system. Pay attention to the technical terms because they matter and once you master them, you’ll see your business in the black at all times.

Action Step 1: Create Five Foundational Accounts

Your first step is to create FIVE accounts. Income, of course, is one, but that’s a “holding” account. Besides these, you’ll create four other checking accounts, which include:

-

- Income

- Owner’s Comp

- Tax

- OPEX (operational expenses)

All your deposits will go into the Income account, which includes check deposits, credit card, or Automated House Clearing payments.

Besides these, you’ll also set up two more accounts as savings accounts. These are “no temptation” accounts and they include Profit Hold and Tax Hold. You should link these directly to the original checking accounts (Profit and Tax, respectively).

You’ll also need two banking institutions. Your “primary” bank gives you easy access to view and transfer. This is where Income and OPEX, for example, will live. Your secondary banking institution should offer you no such convenience.

Action Step 2: Determine Your Allocation Percentages

Now that you’ve set up the accounts, the big question is, “What goes into these accounts?” Yes, money. But how much money?

That’s where allocation percentages come in. Remember, it’s all about maintaining sequentiality and consistency.

For this, Michalowicz points you to “TAPs” or “Target Allocation Percentages and “CAPs” or Current Allocation Percentages.

Most businesses try and take 20% right away and it’s a rookie mistake.

Instead, you want to start modest and get bolder (and, by extension, leaner) over time.

- Target Allocation Percentage: the targets you’re moving towards. They’re not your starting point, they’re progressive goals you want to reach. You can set this at 20%. It’s your “CAP” that will help you get there

- Current Allocation Percentage: where your business sits today. You can begin at 5% and slowly, over time, move the percentage allocation until you reach TAP. If you’ve never given yourself any kind of profit, for example, your “current” allocation percentage would be 0. So an improvement might be 5% and your TAP for this profit account might someday be 20%.

You’ve done all the work, so you should get paid. Profit, Income, OPEX, and Tax are obvious enough. But what about Owner’s Comp? If you’re not in a habit of paying yourself first, Owner’s Comp might be the hardest account to populate.

But populate you must.

Owner’s compensation, as its properly known, is essentially the salary you pay yourself and other equity owners for the work you do. Pay yourself based on the value of the tasks you’re doing 80% of the time and what you might pay someone for those tasks in your industry.

Note: Whatever the percentage of Revenue you set as your Owner’s Comp TAP must at least cover the draw. From here, make the percentage one and one-quarter more the amount of the total salary draws, just in case.

Finally, your Tax TAP is a little more complicated. That’s because, as your revenue increases, so does your tax rate. So how do you set the right TAPs and even CAPs for this account? Simple: You do the math.

- Pull out your personal and business tax returns and add the tax figures up. Set this against your “real revenue” (which is top line revenue less materials and subcontractors). Do this process for the previous two years to give a better picture of your likely tax burden for the upcoming tax year

- Consult your accountant for the estimated tax burden figure, and run this process against real revenue

- Use 27.5% if you’re an Australian-based small business

Putting Profit First Into Motion

Day One

The primary goal is to inform your team and then create a new, automatic routine right away. Adjust the current percentages each quarter until you arrive at TAPs for each account.

-

- Tell your people

- Set up your accounts. For easy recall, give each account a nickname with “CAP” and “TAP” in parentheses. So Profit, for example, might be “Profit 5% (TAP 10%)”

Week One

-

- Cut expenses: Hit the most “frivolous” and obvious expenses such as unused, recurring memberships, office space, expensive cars, or “extra” staff. Remember that everything needs a balance so if you allocated 3% in each of Profit, Tax, and Owner’s Comp accounts, your Expenses need to also decrease by 3%.

- Add up all expenses and multiply by 10%: You need to start building cash reserves so it’s better to be more aggressive at this point.

Twice a Month: The 10th and the 25th

Now that you’ve dealt with the Tax account and the setup of your system, it’s time to deal with your OPEX or operating expenses. Again, systems are your friends here, so the 10th and the 25th of each month will serve as your markers.

Here are the actions you’ll take:

-

- First, deposit all revenue into your INCOME account

- Second, transfer the total deposits from the previous two week period on the 10th and 25th to each of the four accounts (based on CAPs)

- Third, transfer allocated percentages to your Tax hold and Profit hold (savings) account at the 2nd banking institution

- Fourth, pay yourself (Owner’s Comp) and any other’s holding equity. Do not go’beyond what you’ve allocated as your biweekly salary

- Fifth, it’s finally (and only now!) time to pay the bills. Anything you have leftover is for bills. And if you don’t have enough money to cover your bills, that’s a HUGE red flag! Work to clear this by cutting debt and expenses, because you’re clearly spending more than you make.

Quarter One

Your first quarter is a cause for celebration. Do so by cutting yourself a profit-distribution check, at 50% (leave the other half alone). It comes from the Profit account.

You’ll also be paying your quarterly tax amount.

Quarters are a great time for review. So take time to evaluate your current allocation percentages and consider if (and how) you can move them to your TAP’s.

Year One

Year One is also a fantastic time to review how your first year went with the Profit First method and the steps you took to put them into action.

At this point, most businesses find out that they either overshot the mark and were far more conservative than they needed to be (which is not a bad thing at all!). Or else they realize that their tax allocations fell short and they didn’t save a big enough percentage.

That’s a-okay. Since you’re still testing and learning the system, this is the ONE exception to the Profit First method and rule: Pull from your profit account and then adjust the Tax account CAP (and TAP) to make sure you hit all your targets next year.

Download our FREE Profit First calculator

We have built a fantastic Profit First calculator. Its been designed for Australian conditions and takes into account GST, PAYG and other amounts. Click here to download.

Wondering how to start a microbrewery in Australia? Australian support and awareness for craft brews is at historically high rates. This is lucky news for aspiring microbrewery owners. The market has clear demand for new and exciting tastes from indie brew businesses. When starting a microbrewery in Australia, you’ve got a good chance of success, especially if you approach starting your craft brew business with solid knowledge and planning.

Read on for a complete overview of the tax and accounting requirements for setting up a craft brew business in Australia. You’ll learn the unique licensing, permit, and tax requirements for craft brew businesses, and how to create a successful business plan.

Need help on getting the accounting and tax set up for your business? Give James a call directly on 0404 530 563 or email me at james@jdscott.co for a FREE 30 minute consultation on the next steps. You will walk away with three actionable steps to make you profitable, improve your cashflow or fix you tax.

What’s Required to Start a Microbrewery in Australia?

There are many similarities between any startup and a microbrewery in Australia. Any new business should start with a comprehensive business plan. Under any conditions, you meet multi-industry requirements for legally registering your business name and obtaining a tax file number. However, there are some unique requirements for licensing, excise tax, and product labelling that are unique to craft brew businesses.

The specific requirements for craft beer industry in Australia include:

- Obtaining a Producer/Wholesaler’s License from the Office of Liquor, Gambling, and Racing

- Determining and paying applicable excise tax rates

- Following regulatory requirements for beer labelling via The Australian and New Zealand Food Standards Code

In addition to these mandatory requirements for craft brew businesses, there are several other requirements which apply if you intend to serve beer on-premises to members of the public in a pub setting. You may choose to:

- Obtaining a Microbreweries drink on premises license

- Authorisation for trade shows or events

- Obtaining a Responsible Service of Alcohol (RSA)

- Completing Licensee & Advanced Licensing Training

Each of these licensing requirements are discussed in-depth below, along with insight about typical costs and requirements.

Create a Microbrewery Business Plan

An effective microbrewery business plan will encompass both general planning and market analysis, and elements of business plans that are specific to the craft brew industry. The business plan is an opportunity to document your intentions for technical brewing, sourcing beer ingredients, branding, marketing, and complying with all applicable laws.

There are over 600 independent, registered craft brew businesses in Australia, according to the Independent Brewers Association (IBA). A new craft brew business opens every six days. There’s growing demand for craft brew products among Australian locals. However, there’s also fierce competition. A successful, comprehensive business plan is the first step toward a successful microbrewery business.

Starting a microbrewery: the importance of a business plan

What Goes into a Business Plan?

You can begin drafting your business plan using a free, online template or create your own document from scratch. In general, every business plan for a craft brew business or microbrewery should include the following information:

- Summary

- Goals & Objectives

- Microbrewery summary

- Ownership

- Market research

- Strategy

- Regulatory requirements

- Financial analysis

Perform Market Research

There’s more to a successful craft brew business than great-tasting products. Market research is a valuable activity for all new craft brew businesses to understand the industry, competition, and customers. Recommended areas of market research for any new business in Australia include:

- Customers

- Competition

- Products

- Suppliers

- Business Location

- Local Community

In addition, it’s wise to work to develop a deeper understanding of the craft brew business climate:

- Research the microbrew industry

- Connect with successful craft brew entrepreneurs

- Improve your technical brewing knowledge

Research Regulatory Requirements

The business plan should involve thorough research and documentation of all applicable regulations to produce, sell, distribute and label craft beer products. In addition, your regulatory requirement research should include comprehensive look at tax requirements. The regulatory requirements for craft brewers are discussed later in this article. However, these are an overview, not a definitive guide to regulatory compliance.

It’s up to you to stay informed on all applicable laws and adjust your business plan when legal requirements change. A business plan should be a living document, and craft brew entrepreneurs should be aware that laws can change quickly.

Perform Cost Projections

Budgeting and financial forecasting is a crucial part of business plan creation for microbreweries and any other small business. After all, your business needs a solid financial plan to succeed in a competitive craft brew marketplace. The Small Business Development Corporation offers numerous free tools online to guide aspiring business owners through financial planning activities. Your cost and financial analysis should include:

- Startup Costs

- Legal fees

- Accounting fees

- Permits

- Licenses

- Wages

- Real estate

- Equipment

- Sales forecasts

- Expense projections

- Cost of goods

- Cash flow projections

Register Your Business

For a comprehensive discussion on taxes in Australia, read this article.

ABN Registration

An Australian Business Number (ABN) is a free, 11-digit number from the Australian Government’s Business Registration Service. This number is not used for taxes, but it used to create a unique identifier for your business in the community. An ABN is used to:

- Prove business identity in ordering and payments

- Avoid pay as you go tax (PAYGT)

- Claim goods and service tax credits

- Claim energy grant credits

- Receive an Australian domain name

If you are starting an enterprise, such as a microbrewery, you are entitled to an ABN. To help work out which business structure will work best for you click here.

There are a few simple requirements to register for an ABN. Generally, the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) will review an ABN application within 20 days.

Business Name

An Australian Business Name, or ACN, is the official name of your microbrewery. First, check name availability o the free ASIC search function. If the chosen name is available, you can nationally register your business name.

The cost of registering your business name with ASICs is $36 for one year, or $85 for 3 years. The ACN application is approved within 2-5 days, depending on the payment method used during registration.

ACN registration is not the same as a trademark. It also does not entitle you a domain name. Before you submit an ACN application, it’s wise to verify availability. Use IP Australia search to make sure you’re not going to infringe on any registered trademarks. Applying for a Trademark with IP Australia costs $520 and involves a multi-step application process with a final answer within 13 weeks. A web registry service search can reveal potential domain name availability and costs.

Tax File Number (TFN)

A Tax File Number is a unique identifier issued to businesses and individuals by the ATO. Generally, the free application for a business TFN can be completed during the same application process as an ACN and ABN.

Licensing and Permits

Produce/Wholesalers License

This license be obtained from the Office of Liquor, Gaming, and Racing. The license permits craft brew businesses to sell product to other licensees, sell product to the public, and conduct product tastings. It is not the same as a permit to serve beer or food in an on-site pub, but it can permit you to serve samples to customers during a brewery tour.

Retail takeaway sales to the public are subject to specific hours under this license, unless you apply for extended trading hours. This license permits trading between:

-

-

-

- 5am-10pm Monday through Saturday

- 10am-10pm Sunday

-

-

There are specific information requirements to submit an online application for this license. You will need to submit a floor plan, any applicable local counsel approval, requested trading hours, and contact information. Costs vary according to the Liquor Fee Schedule, however the application and processing fee for small microbreweries is generally $385.

An extended trading hours application can be made to extend Sunday hours from 5am to 10pm. Licensees are subject to a 6-hour daily closure requirement, even with an extended hours permit. However, special applications can be made to temporarily or permanently exempt your brewery from the 6-hour closure requirements if you can demonstrate benefit to patrons and a plan to sell alcohol safely to the Liquor & Gaming NSW.

Responsible Service of Alcohol Training

Responsible Service of Alcohol (RSA) training and certification is required for all owners and staff prior to applying for the Product/Wholesalers License. RSA training from an approved provider and valid NSW cards are an ongoing requirement for all staff of the microbrewery. A RSA refresher course must be completed every five years. The costs of training vary by provider, but $140-160 is average.

Licensees and managers of microbreweries are required to undergo two additional training courses to obtain and maintain a Product/Wholesalers license under the 2018 Liquor Regulation.

Licensee Training & Advanced Licensee Training

You can verify your training requirements on the Liquor & Gaming NSW website. However, both types of training are generally required for licensee applicants after September 1, 2018. Complete training through an approved provider to obtain this competency. Some fully online options are available. Costs and time commitment can vary depending on the provider you select, but you can expect to pay approximately $350 for each competency and spend 6-7 hours per class.

Microbreweries and Small Distilleries Authorisation

The Liquor & Gaming NSW is currently piloting a trial programme for a special type of drink-on-premises authorisation for microbreweries and small distilleries. This permit allows craft brew businesses to sell products to the public for consumption on-premises in the context of a restaurant or pub, not just tastings. There are some qualifying criteria, including a patron limit of 120 guests and providing food service in addition to beer.

This application can be completed simultaneously with a new application for a Producer/Wholesaler License. Licensees are subject to limited trading hours, including:

-

-

-

- 5:00am-midnight, Monday through Saturday

- 10:00am-10:00pm, Sunday

-

-

There is no cost to apply for this license through August 31, 2020. According to the Liquor & Gaming website, there are plans to reevaluate this licensing pathway during 2020 to potentially refine the program and expand requirements.

Industry Liquors Show and Producers Market Authorisation

Selling liquor at a tradeshow, food show, or another event generally requires a special authorisation from the Liquor and Gaming NSW. Selling craft brew at an event with 2,000 or fewer people requires a Limited License for Trade Fairs, which can be obtained by an individual with valid RSA credentials. If attendance is expected to exceed 2,000, you will need an individual application for a Large Scale Commercial Event. Costs range from $165-$650, depending on attendance.

Local Notices

The application for a Producers/Wholesalers license requires local notices. These notices must be lodged either prior to application, or within two days of filing a Producer/Wholesalers license application.

-

-

-

- public consultation ? site notice;

- police notice; and

- local consent authority notice.

-

-

Prepare to Pay Taxes

Want an easy way to ensure you never run out of cash to make a tax payment? Have a read of our simple solution to this all too common problem.

Australian business tax requirements are administered under the ATO, and in some cases, state revenue offices. It’s important to understand your requirements to avoid penalties and any tax concession rates. Your tax liabilities are likely to include:

-

-

-

-

- ATO company tax rate ? currently a

- for 2021-2022

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Capital gains tax, paid as part of income tax on any asset disposals

- Goods & services tax, and any applicable GST tax concessions

- Payroll tax

- State & territory tax responsibilities, if applicable

-

-

In addition, craft brew businesses are subject to ATO excise tax rates for alcohol, which are subject to update on February 3, 2020. These tax rates are calculated based on litre of alcohol (LAL).

Create Systems for Records-Keeping

Systems of record (SOR) for business and tax records are a responsibility to pay proper tax rates and tax advantage of all possible concessions. Your systems should include a centralised method to securely store, track, and retrieve records for:

-

-

-

- Receipts

- Expenses

- Sales

- Taxes

- Tax invoices

- Wages and salaries

- Purchase records

-

-

Not only do you need to capture these records, you need to meet legal requirements to retain information. In general, records must be retained for 5 years.

Alcohol Labelling

Pre-packaged beer and alcohol must comply with all legal requirements for labelling. Beer sold in Australia l is subject to labelling laws from the following authorities:

-

-

-

- Food Standards Australia and New Zealand

- Department of Agriculture and Water Resources

- State and Territory Food Regulations

- Australian Competition and Consumer Commission

- National Measurement Institute

- Alcohol Beverages Advertising Code Scheme

-

-

Failure to comply with all applicable requirements for labelling can result in serious consequences, including product recall or prosecution. There are historical examples of prosecution and fines imposed against craft brew businesses for non-compliance with labelling, including labels which were deemed misleading or false under the ACCC.

Mandatory Label Information Includes:

-

-

-

- Product Description (Standard 1.2.2)

- Volume Statement (National Trade Measurement Regulations)

- Alcohol Content (2.7.1)

- Standard Drinks Statement (2.7.1)

- Country of Origin (ACCC)

- Supplier & Packer Name and Address (1.2.2)

- 10C Refund Statement (Australian Beverages Council)

- Best-Before Date (1.2.5)

- Pregnancy Advisory (DRIS)

- Lot Identification (1.2.2)

- Sulphites & Allergens (1.2.3)

- Other Use of Ingredients (1.3.1, 1.3.3, 1.4.4, 1.5.1)

-

-

Legal Requirements for Non-Mandatory Label Information:

The following labelling elements are generally helpful. When applicable, any standards are linked.

-

-

-

- Brand Name

- Responsible Drinking Message (DrinkWise)

- Barcode (GS1)

- Recycle Logo (Planet Ark)

- Ingredients List (1.2.4)

- Nutrition Information Panel (1.2.8)

-

-

Protect Against Liabilities

It’s costly to scale your passion for craft brew beyond a home hobby to a microbrewery business. It’s even costlier if you fail to protect your new business from the various liabilities. An estimated 87% of small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) believe a liability could put them out of business. The smartest time to protect your business is before you’re facing a claim.

Insurance

The production, manufacturing, distribution, and sales of craft brew can introduce a number of liabilities, including the possibility of exposure via property, employees, products, or customers. Insurance coverage should minimise your financial risks if you experience an unexpected event such as property damage, a product recall, or an on-site injury.

-

-

-

- Property & Asset Insurance

- Public & Products Liability Insurance

- Workers Compensation Insurance

- Commercial vehicle insurance, if applicable

-

-

Tax liabilities

Australian business tax liabilities are more than complex than paying a simple 27.5% on profit. There’s many concessions available, especially to small business owners. It’s a risk to profitability to either underpay or overpay your taxes to the ATO and local territories. Protecting your business against tax liability requires strong systems for records-keeping and knowledge of liabilities. For many aspiring microbreweries, working with a small business tax specialised accountant is the best way to avoid risk exposure through tax mistakes.

Trademarks

A trademark is used to distinguish your business and products from other businesses. Trademarking your business name, logo, and craft brew names can protect your brand from competitors and copycats. Researching the trademark process on IP Australia can provide insight into the benefits of trademarking your name, brand, and beers. It’s possible to manage your own trademark applications, but many new microbrew businesses choose to work with a trademark attorney on this process.

Knowledge is a Launchpad to Microbrewery Success

If you’ve got a solid stash of craft brew recipes and some technical knowledge of brewing, you’re at a huge advantage for starting a microbrew business. When craft brew knowledge is coupled with knowledge of the business and legal requirements for Australian business, you’re in a nearly-unstoppable position. Creating a business plan should involve a heavy investment into researching the industry, your target market, and all applicable requirements for licensing, labelling, taxes, and records-keeping.

You can protect your business against liabilities and risks by partnering with an SME consultant who specialises in craft brew startups. JD Scott + Co is the leading resource for Australian accounting, advisory, and tax help for fledgling microbrew businesses.

JD Scott + Co is one of Sydney’s leading Chartered Accounting firms, we aim to help build your business and wealth, empowering you to reach your goals.